solar panel incentives

Introduction

Going solar isn’t just an environmental choice; it’s a financial strategy that can stabilize your energy costs for decades. Incentives, tax credits, and utility programs can lower the upfront cost significantly, but the rules can feel like a maze. This article translates the jargon into plain language, walks through real-world numbers, and gives you a step-by-step plan to evaluate if home solar fits your roof, budget, and goals.

Outline

• The incentive landscape: federal, state, local, and utility programs

• Home solar planning: sizing, costs, and site considerations

• The solar panel tax credit: eligibility, timing, and documentation

• Financing and payback: cash, loans, leases, and performance incentives

• Conclusion and action plan: how to move from research to installation

1) The Incentive Landscape: How Federal, State, and Utility Programs Work Together

Solar incentives operate like puzzle pieces that, when assembled, can transform a large price tag into a manageable investment. Broadly, homeowners encounter four layers: federal tax incentives, state programs, local or county rebates, and utility offerings. While the details vary by location, the interplay is consistent: the federal credit reduces your income tax liability by a percentage of the project cost, while state and utility programs can reduce the price you pay or reward the energy your panels produce. Understanding the order of operations matters, because some benefits are calculated after others are applied.

At the federal level, a residential clean energy credit currently covers a notable portion of eligible costs. This typically includes panels, inverters, racking, balance of system hardware, labor, permitting, and interconnection fees. Energy storage can also qualify when meeting capacity requirements. The credit does not arrive as a check; it offsets federal income taxes, and in many cases unused credit can be carried forward to future tax years. This mechanism is why timing your installation in relation to your tax situation can be helpful.

States add their own layers. Some offer one-time rebates that reduce upfront cost. Others provide performance-based incentives (PBIs) or renewable energy certificates you earn for each unit of solar generation. In markets with tradable certificates, homeowners can sell them to support recurring revenue, though prices fluctuate with policy and demand. Property tax considerations are another piece: many jurisdictions exclude the added value of solar from property tax assessments, helping preserve your annual housing costs.

Utilities can offer bill credits for exported solar energy through net metering or net billing programs. Net metering typically values exported electricity at the retail rate, while net billing often uses a lower export rate; the difference influences how fast you recoup your investment. Time-of-use rates, demand charges, and fixed fees further shape your savings. Because rules evolve, it’s wise to review your utility’s current tariff and interconnection requirements before signing any contract.

Key takeaways homeowners often find useful include:

• Incentives stack, but they do not always stack in the same order; read each program’s rules.

• Performance incentives reward production over time; rebates reduce initial cost.

• Export credit structures (net metering vs. net billing) meaningfully impact payback.

• Property and sales tax exemptions can quietly add hundreds or even thousands in value.

2) Solar Panels for Home: Costs, Sizing, and Site Considerations

Designing a home solar system starts with your electricity use. A common benchmark for a detached home in many regions is roughly 8,000 to 12,000 kilowatt-hours per year, but your bills tell the real story. Gather at least 12 months of usage to capture seasonal swings. From there, a designer estimates required system size using local solar resource data. A 6 to 8 kilowatt array often covers a typical household’s annual use, though cloudy climates, shading, electric heating, or an electric vehicle can push the size higher.

Installed costs vary by region, labor market, and equipment selection. A realistic pre-incentive range for residential rooftop systems in many parts of the United States is around $2.50 to $4.00 per watt. That means a 7 kilowatt system might be quoted between $17,500 and $28,000 before incentives. After the federal tax credit and any state or utility programs, the net price can drop substantially. Batteries add flexibility for backup power and rate optimization, and they commonly add several thousand dollars depending on capacity.

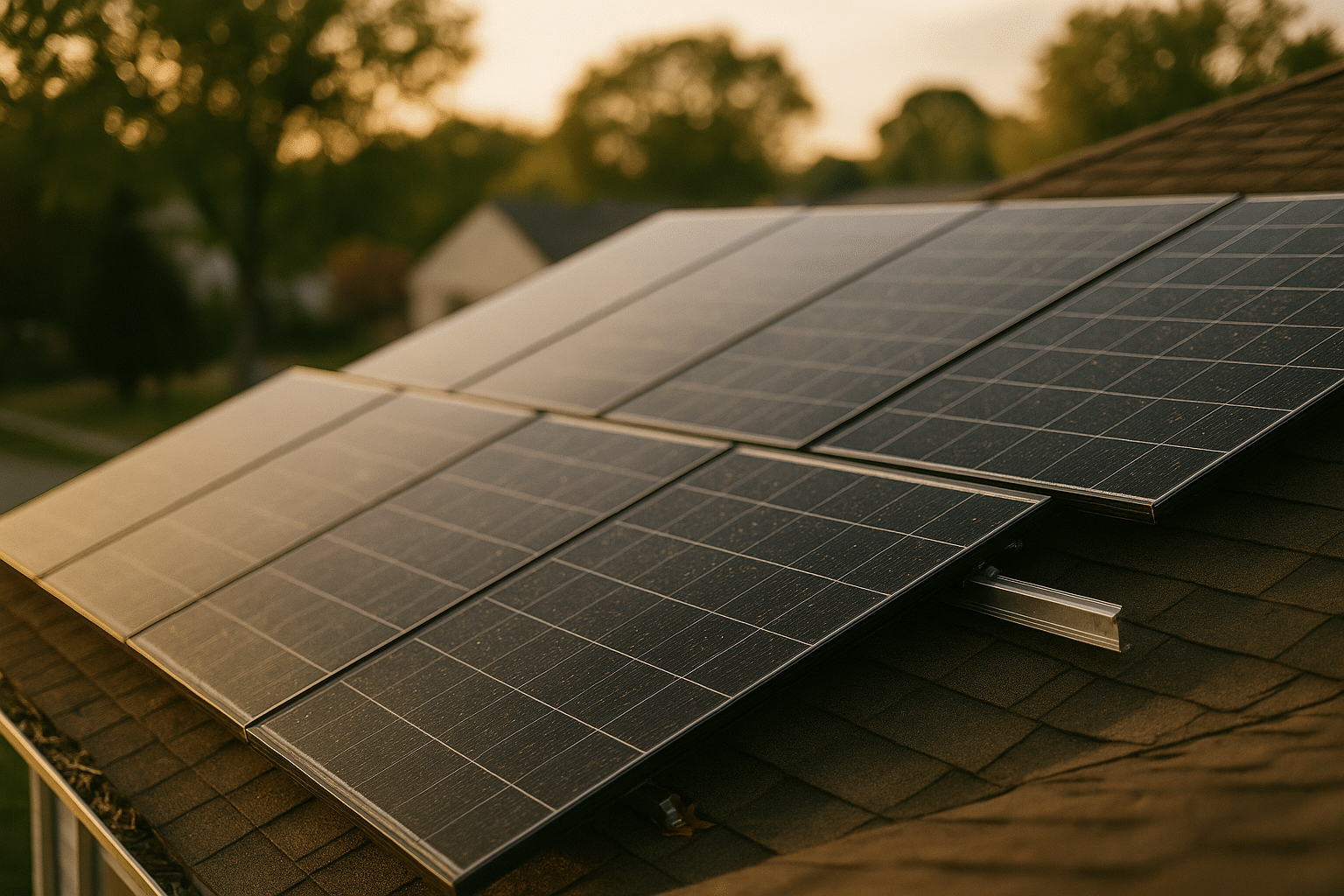

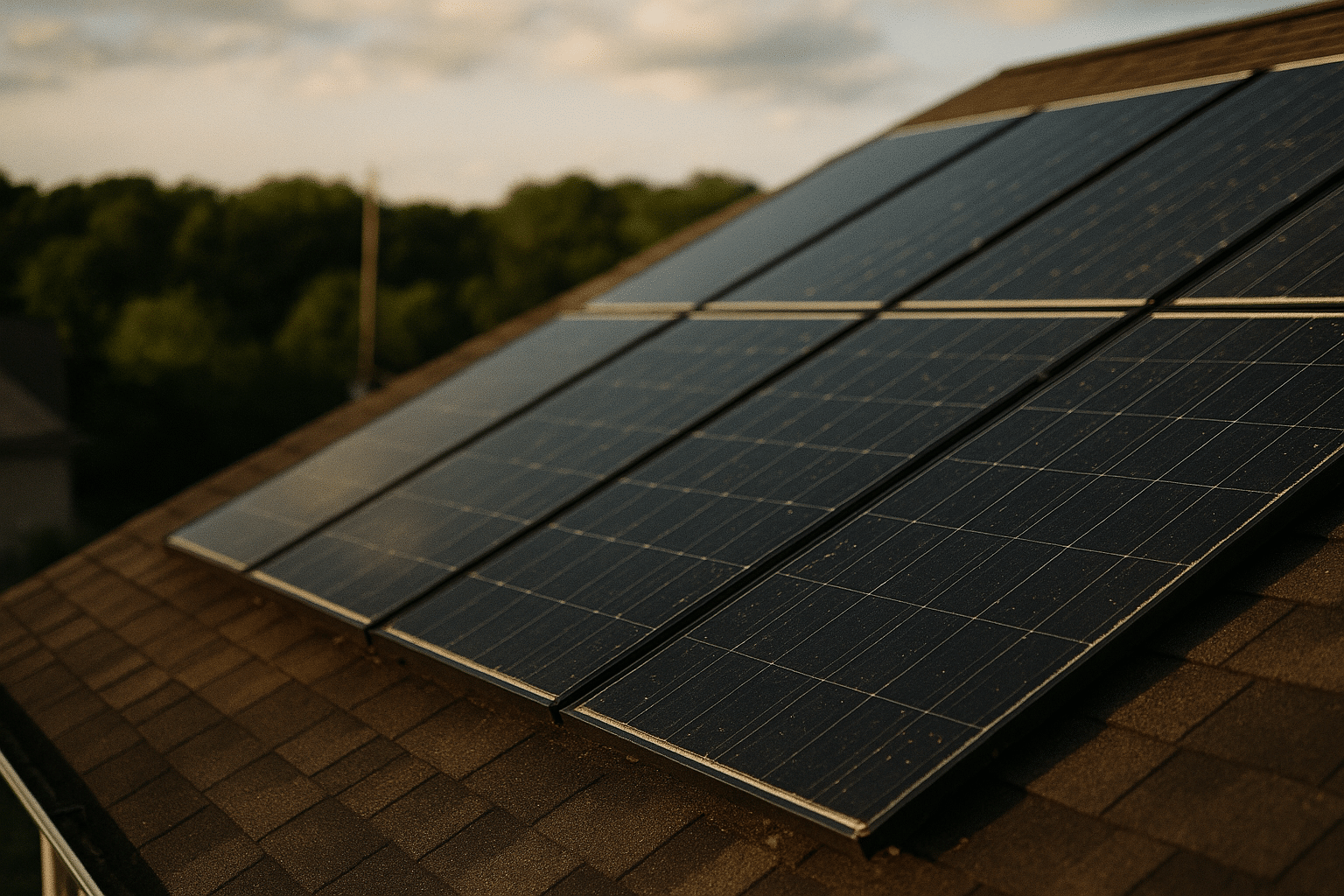

Site suitability is as important as price. South-facing roofs with minimal shade and pitches between about 15 and 40 degrees are generally efficient, but east/west orientations can still perform well with slight increases in capacity. Shading from chimneys, trees, or neighboring structures can reduce production; professional shade analysis uses tools to estimate annual losses and guide placement. Roof condition matters too: if your shingles have limited life remaining, consider replacement before installation to avoid future removal and reinstallation costs.

Panel and inverter choices influence aesthetics and performance. Higher-efficiency modules can produce more energy per square foot, which helps on smaller roofs. Microinverters or optimizers can mitigate the impact of partial shading and allow panel-level monitoring. String inverters remain a solid, cost-effective choice when shading is minimal. Differences in warranty length, product coverage, and workmanship protections are meaningful; review terms carefully rather than focusing solely on nameplate wattage.

Practical tips for homeowners include:

• Use 12 months of bills to size the system; add a buffer if you plan to electrify heating or transportation.

• Ask for a shade report and an energy yield estimate in kilowatt-hours, not just panel wattage.

• Compare contracts on total cost per watt and total kilowatt-hours expected in year one.

• Consider battery storage if you have frequent outages or time-based utility rates.

3) The Solar Panel Tax Credit: Eligibility, Timing, and Documentation

The federal residential clean energy credit is a cornerstone incentive for homeowners, covering a significant percentage of eligible project costs. To qualify, the property must be a residence you own (primary or secondary in most cases), and the system must be placed in service during the tax year for which you claim the credit. Eligible costs commonly include equipment, labor, permitting, and interconnection fees. Energy storage systems that meet minimum capacity requirements also generally qualify, including many stand-alone batteries installed after the solar array, subject to current rules.

It is important to understand what the credit does and does not do. It reduces your federal income tax liability dollar-for-dollar by the eligible percentage of the project cost. If the credit exceeds your liability in the first year, many taxpayers can carry the remainder forward to future years until it is used up. The credit does not create a refund by itself if you owe nothing, and it is not considered taxable income at the federal level. State tax treatment can differ, so review your state’s guidance or consult a qualified professional.

Documentation is your ally. Keep dated estimates and final invoices with line items for equipment and labor, copies of permits and approvals, interconnection letters, and proof of payment. If your project includes a battery, retain product specifications showing capacity. For multi-year projects, organize paperwork by milestone to make filing straightforward. While this article is informational and not tax advice, many homeowners file the residential clean energy credit alongside their annual return; others work with a tax preparer to ensure accuracy and to plan carryforwards.

Timing strategies can help. If your income varies, consider scheduling your installation for a year when you can absorb more of the credit. If a state rebate lowers your out-of-pocket cost, note that the federal credit generally applies to the net amount you pay, not the pre-rebate price. Conversely, performance-based incentives earned after commissioning typically do not reduce the basis for the federal calculation. Read the fine print for each program, because rules can change and some jurisdictions require pre-approval before installation.

Quick checklist before claiming:

• Confirm ownership structure: direct ownership typically qualifies; leases and service agreements generally do not.

• Verify placed-in-service date with your final approval or permission-to-operate.

• Save all invoices and proof of payment; ensure labor and equipment are itemized.

• If uncertain, consult a qualified tax professional to align credit timing with your broader tax picture.

4) Financing and Payback: Cash, Loans, Leases, and Performance Incentives

How you pay for solar can matter as much as the quoted price. Cash purchases avoid interest and typically deliver the shortest payback. Loans spread the cost over time while preserving eligibility for ownership-based incentives. Leases and service agreements can reduce or eliminate upfront expense, but they often shift key incentives to the provider and may include escalators that affect long-term savings. Weighing total cost of ownership over 20 to 25 years, rather than focusing on monthly payment alone, leads to clearer decisions.

Consider an example. Suppose a 7 kilowatt system is quoted at $21,000 before incentives. If you claim a 30% federal credit, your tax reduction could be up to $6,300, making your effective net cost $14,700, assuming sufficient tax liability. In a location that yields about 1,400 kilowatt-hours per kilowatt annually, the system could produce roughly 9,800 kilowatt-hours in year one. At an average electricity rate of $0.18 per kilowatt-hour, that offsets about $1,764 in bills before any fixed charges. Ignoring rate inflation and degradation for simplicity, payback would be around 8 to 9 years; increases in electricity prices or performance incentives could shorten that timeline.

Financing choices change the math. A low-interest secured or unsecured loan can keep net cash flow near neutral if the monthly payment approximates your bill savings. Higher-interest loans extend payback and raise total interest paid. Leases and service agreements often include a set price per kilowatt-hour or fixed monthly payment with an annual escalator; this can be attractive when you value predictability and maintenance coverage, but it may deliver smaller long-term savings than ownership.

Performance incentives can enhance returns:

• Net metering credits exported energy at or near the retail rate in many areas, improving payback.

• Net billing compensates exports at an avoided-cost or time-based rate; pairing with a battery can help self-consume more energy.

• Renewable energy certificates or production incentives, where available, add a modest revenue stream but may fluctuate with policy and market demand.

Before signing, request a transparent pro forma showing:

• Total project price, incentives assumed, and the calculation order.

• Expected year-one production and the degradation rate used in the model.

• Utility tariff assumptions: export rate, time-of-use windows, fixed charges.

• Loan or agreement terms: interest rate, fees, prepayment policy, escalators, and maintenance responsibilities.

5) Conclusion and Action Plan: Turning Incentives and Credits Into Real Savings

Home solar is both a numbers exercise and a quality-of-life decision. Incentives and the federal clean energy credit can substantially reduce costs, while smart design and financing can align monthly cash flow with your budget. The key is to turn abstract policy into a concrete plan tailored to your roof, utility rates, and tax situation. With a structured approach, you can minimize surprises and capture the value on the table without overextending your finances.

Start with a simple seven-step action plan:

• Audit your usage: download 12 months of bills and note seasonal peaks, demand charges, and any time-of-use windows.

• Check your roof: estimate remaining roof life, identify shading sources, and note available area for panels.

• Map incentives: confirm federal credit eligibility, research your state’s rebates or production incentives, and review utility export rules.

• Gather bids: request at least two proposals that include total cost, expected kilowatt-hours in year one, and a shade report.

• Compare financing: model cash, loan, and service-agreement scenarios with the same production and rate assumptions.

• Validate timelines: understand permitting, interconnection, and equipment lead times; ask about required pre-approvals.

• Document everything: save quotes, invoices, approvals, and payment records so claiming incentives is straightforward.

As you evaluate proposals, prioritize clarity over flash. A precise energy yield estimate, a realistic degradation assumption, and a clear explanation of export credits are more valuable than glossy imagery. Ask providers to show how they applied incentives in their calculations and to separate assumptions from guarantees. If a projection hinges on high export rates, test the sensitivity with a lower rate or with partial self-consumption through load shifting or a battery.

Finally, align the project with your long-term plans. If you expect to add an electric vehicle or convert a gas appliance to electric, size the system with modest headroom or plan for a future add-on. If your goal is resilience, evaluate whether a battery’s backup capability justifies the additional cost in your area. When incentives, careful design, and realistic modeling come together, home solar can deliver steady financial value and a quieter, cleaner energy experience for years to come.